Children’s classics in translation can contribute to nurturing threatened languages and bringing dormant ones back to life

by Pisana Ferrari – cApStAn Ambassador to the Global Village

A growing movement of language activists, cultural stakeholders, and scholars across the world is seeking new ways to preserve endangered languages and bring dormant ones back to life, through everything from digital dictionaries and apps, to cultural events such as language arts festivals and films screenings. Children’s literature can be a powerful tool in promoting language and literacy development, and the translators of the recent te re Māori versions of “The Hobbit” and “Alice in Wonderland”, and the Latin version of “Geronimo Stilton”, hope their work will contribute to this worthy cause.

“The Hobbit” and “Alice in Wonderland” in te reo Māori

Tom Roa, associate professor of Māori and Indigenous Studies at the Waikato University, is currently translating J. R. R.Tolkien’s 304-page tale “The Hobbit” into te reo Māori, and hopes to complete it by the end of the year. In a recent interview Roa says that as a young boy the novel captured his sense of adventure. He wants to reproduce the same sense of wonder he experienced then, while continuing to revive the te reo Māori language. “The Hobbit” is set within a fictional universe and follows the quest of the protagonist, hobbit Bilbo Baggins, to win a share of a treasure guarded by Smaug the dragon. Hobbits are creatures resembling very short humans but with furry feet, who live in underground houses and are mainly pastoral farmers and gardeners. Roa is now looking for suitable names for the vast array of elf, dwarf and orc names in the novel. For Thorin the dwarf he is playing with the name Torino, because rino is the Māori word for iron. As he is one of the toughest of the dwarfs, says Rea, the translation will give it that kind of reflection.

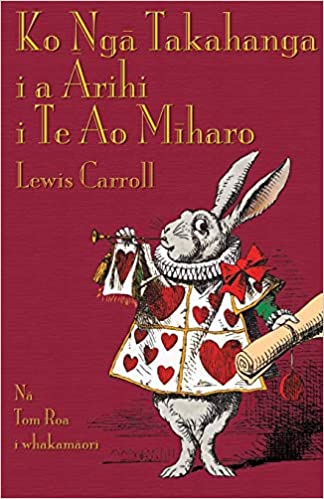

Roa has previously worked on a translation of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”. “Ko Ngā Takahanga i a Ārihi i Te Ao Mīharo” was published in 2015, and donated to a number of kura kaupapa, Māori schools. “Alice in Wonderland” and “The Hobbit” have these amazing turns of phrases in English and if I am able to translate those turns of phrases using Māori idiom, I think we may be able to awaken something else within the Māori audience”, says Roa.

Books in te reo Māori are still a small area of the children’s book market, but one of great growth, according to the Children’s and Youth Services coordinator for Wellington City Libraries. The WCL has nearly 550 te reo Māori titles with around 2.700 copies in circulation, across its 14 branches.

In recent years there has been a very succesful Māori “renaissance” movement in New Zealand, also thanks to state interventions and legislation. The Māori language has become increasingly popular as a common national heritage even among New Zealanders without Māori roots.

“Geronimo Stilton” and other children’s books in Latin

The book “Mihi nomen est Stiltonius, Hieronymus Stiltoniusis”, Latin for “My name is Geronimo Stilton”, is hot off the Edizioni PIEMME press (December 2020). It is the translation of the very first book about this much loved fictional character, created in the year 2000 by Elisabetta Dami, an Italian children’s books author. Geronimo Stilton is an anthropomorphic mouse who lives in the fictional New Mouse City, who works as a journalist and editor for the fictional newspaper The Rodent’s Gazette. The occasion is the celebration of 20 years since the first book came out. The publishers say that Latin is an ancient but universal language that can still tell a funny, modern adventure story. The Geronimo Stilton book series has become a global phenomenon with 170 million books sold worldwide, in 50 languages, and 3 animated series distributed in over 130 countries.

The Latin language has been used in translations of a large number of other children’s books. A dedicated Wikipedia page lists 120+ works of modern literature in Latin, about 80% of which are books for children. Recent titles include novels by Marjory Wililams (“Velvetinus Cuniculus”, “The Velveteen Rabbit”, 2020) , Edgar Allan Poe (“Persona Mortis Rubrae”, “The mask of the Red Death”, 2018), and Mark Twain (“Pericla Thomae Sawyer”,”The Adventures of Tom Sawyer”, 2016 ). Classics such as “Pinocchio”, “Robinson Crusoe”, “The Little Prince” and “The Christmas Carol”, as well as modern best sellers like the Harry Potter series, have also been translated into Latin.

Other notable efforts to keep the language alive include the Latin versions of Wikipedia (Vicipaedia) and of Google Translate, the 40+ active Latin Facebook groups, the monthly Latin Radio Bremen (DE) bulletin and the Vatican’s “Hebdomada Papae” (news bulletin in Latin). Duolingo’s Latin course, launched last year, has 1.4 million active users (“If you want get in touch with the toga-wearing senator that lives in your heart, we’ve got the language for you. Salvete!”). Latin remains the official language of the Roman Catholic Church — the Pope has a Twitter account in Latin with almost 1 m followers — and of the Vatican State.

See also our articles on “Finland’s longstanding contribution to the contemporary study and use of Latin” and “Is Latin still relevant in today’s world?”

Sources

“The man translating The Hobbit into te reo Māori”, Ellen O’Dwyer, Stuff online magazine, January 10, 2021

“Geronimo Stilton is now in latin too!”, LicenceGlobal, December 7, 2020

Background info

“How to Resurrect Dying Languages”, Anna Luisa Daigneault, Sapiens Anthropology magazine, 18 December 2019

“Preserving languages in the new millennium: indigenous bilingual children’s books.” The Free Library. 2014 Association for Childhood Education International 28 Jan. 2021

Photo credits: Amazon