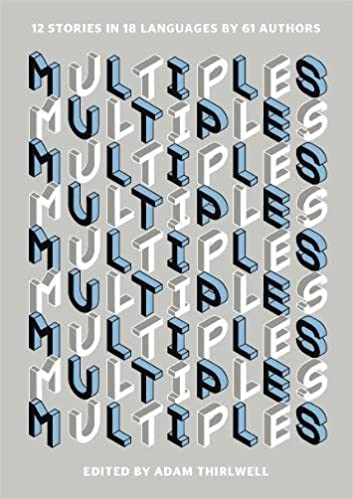

“Multiples”, 12 short stories in 18 languages by 61 authors, a captivating experiment in translated literature

by Pisana Ferrari – cApStAn Ambassador to the Global Village

“Multiples”, is an anthology of multiple translations edited by world-acclaimed British novelist Adam Thirlwell and published in 2013. Thirlwell chose 12 stories, written in Danish, Spanish, Dutch, Japanese, German, Arabic, Russian, Serbo-Croat, Italian, Hungarian and English, and asked the sixty-one writers who accepted to take part in this “literary game” to follow a precise set of rules. The first writer was to translate a story into English, which a second one would then translate into a different language, and a third back into English, and so on, down the line. The writers would each only see the preceding version of the story. As a result of the stories being told and retold, out of English and in again, they were transformed, twisted and turned into something new, and ended up as “an intriguing literary version of Chinese whispers”, says Lucian Robinson, literary critic for The Guardian. (1) The anthology featured a stellar line-up of authors, including Zadie Smith, Alejandro Zambra, Jeffrey Eugenides, Laurent Binet, Javier Marias, David Mitchell, Colm Toibin, Etgar Keret and Sheila Heti. Interestingly, most of them are fiction writers, not translators, and none of the stories were in their original language. Once the rules were made, says Thirswell in the introduction, the exhausted editor’s remaining role was in cajoling these international novelists to work!

If A is translated into B and then C, is C still a translation of A?

Thirswell writes in the introduction that literature is one of the rare arts where the “original” is often experienced as a “multiple”, in the sense of a useful form of mechanical reproduction. This way of thinking, he says, has as a problem in that the relation of, say, a postcard, to a painting, is really not that of a translation to its source. Every novelist will try to be “as singular as possible”, and the medium they possess for this singularity is language: the finished singularity goes by the moniker of “style”. Translation is like an airplane, he adds, and style should be “entirely transportable”. He defines “Multiples” as an experiment which aims to answer the question: What would happen if a story were successively translated by a series of novelists, each working only from the version immediately prior to their own – the aim being to preserve that story’s style? He says the interest is to see how far the stylistic essence of the story, its singularity, could survive such a “stylistic epidemic”. And to see how the initial singularity is transformed into a series of new singularities: the multiple new possibilities created by each new novelist’s style.

A reflection on what is lost and what is gained in translation

The experiment didn’t quite work out as he expected, says Thirswell. “The degree to which each story emerges unscathed veers wildly in each case”; sometimes the hypothesis was neatly confirmed, other times it was “gruesomely demolished”, ultimately leading him to question the very notion of “style”… Writer and translator Daniel Hahn, says that part of the pleasure of translations undertaken serially, as in “Multiples”, rather than in parallel, comes precisely from watching a little distortion or imprecision being compounded, or amplified, as the series progresses. Any translation is a new text built of a thousand tiny choices. But in “Multiples” a reader often won’t know who’s responsible for those choices. Who, after all, can read 18 languages? (I personally can only read three but found the book captivating). Too often, he adds, translation is discussed in terms of loss. Hahn says “Multiples”, refreshingly, does the opposite: it asks, instead, what is it that survives? To anyone interested in translation – or perhaps more pertinently, in the effects of style – each failure is something new, something fascinating, that is gained.” (2)

Indirect translation is often used in publishing for “small” languages

In a blog article titled “The risk of cultural meaning being diluted when translating translations” we wrote about the effects of indirect translation. As not all language combinations are easily available, indirect translation is often used for “small” languages: in this case one translation renders a text from the small language to a large one, and then that translation is used as the basis for all subsequent translations. In the article we did not look so much at style but at how cultural meaning can be diluted or lost. Every time you translate you produce a new text, and that new text is underpinned by certain cultural and linguistic assumptions that are particular to how that language in particular works and relates to the people who speak it. Recourse to indirect translation can also of course lead to positive results e.g. for works from peripheral/distant cultures, which could otherwise never be published.

Excerpt from the Table of Contents of “Multiples”(3)

A Preface to Writing Samples: a story in Danish by Søren Kierkegaard…

translated into English by Clancy Martin…

translated into Dutch by Cees Nooteboom…

translated into English by J.M. Coetzee…

translated into French by Jean-Christophe Valtat…

translated into English by Sheila Heti…

translated into Swedish by Jonas Hassen Khemiri

A brief aside about “back translation”

The book opens with an English text, which is “back translated” to English twice, once from the Dutch version, and once from the French. Technically, “back translation”, as this process is called, is used to compare a translated document with the original for accuracy and quality. In “Multiples” the writers were asked to provide an “accurate copy” of the original, but over the series of translations it was of course challenging to maintain fidelity. The back translation method is used widely in testing and assessment to verify translation quality and accuracy of data collection items, one of our main areas of activity. While it may help detect mistranslations in the translated test, which the test authors can then ask to correct (and request another round of back translation), it does not always ensure that equivalence flaws are identified.

About cApStAn LQC

cApStAn Linguistic Quality Control is a high-profile language service provider with a holistic approach to multilingual projects: this ranges from translatability assessments, preparation of glossaries and translation guidelines-before translation commences-to delivering premium translations that are fit for purpose, and linguistic quality control post translation. The R&D department focuses on in-house development of web-based quality assurance applications and searchable translation memory management.

Footnotes

1. “Multiples: 12 Stories in 18 Languages by 61 Authors, edited by Adam Thirlwell – review”, Lucian Robinson, The Guardian, August 11, 2013

2. “Multiples: 12 Stories in 18 Languages by 61 Authors edited by Adam Thirlwell – review”, Daniel Hahn, The Guardian, August 16, 2013. Amazon entry on “Delighted States”

Photo credit Cover of book, Amazon