Redefining the Concept of “Master Version” in Multilingual Test Items by Mitigating the Anglo-Saxon Legacy

by Pisana Ferrari – cApStAn Ambassador to the Global Village

Functional equivalence of test items across different languages and cultures is essential in order to ensure comparability of data. In the course of our 20+ year experience in linguistic quality assurance (LQA), in particular for major international large scale assessments (ILSAs), we have seen that starting with a “more translatable” source version mitigates language/item effects further down the line. The most common practice is to produce a well-crafted English source version, to pilot it, validate it, and only then adapt it into multiple languages. However, evidence of recurring translation issues in ILSAs suggests that this practice may not be optimal. Tests earmarked for translation into multiple languages often contain idioms and colloquialisms and are replete with ambiguities that cannot be rendered in target languages. The language will often reflect the fact that questions are written mainly by people with UK, US, Canadian and Australian backgrounds, and therefore with an Anglo-Saxon focus. Our suggestion is to follow a standardised adaptation process with a simpler, more international and culturally balanced English source version, reviewed by linguists and subject matter experts from different backgrounds and cultures. These reviews will generate a comprehensive corpus of adaptation notes, on which translation teams can rely to produce target versions, including into idiomatic English for use in English-speaking regions.

Addressing potential language/item effects in a systematic and standardised way

The earliest multilingual comparative studies date back to the late 1950s and early 60s. Examples include the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) pilot project (1959-1961) and the Five Nation Political attitudes and Democracy study by researchers Almond and Verba (1963), and this is when the “Anglo-Saxon practices” gained a lot of traction. At that time equivalence between the different languages was assumed, and it was only when the results were analysed that the language/item effects were revealed. Despite this, and the fact that sophisticated translation designs have become the norm in high-stakes tests, the Anglo-Saxon legacy has prevailed for decades. The LQA processes – both pre- and post-translation – that we have developed at cApStAn help identify any such language/iitem effects in a very precise way.

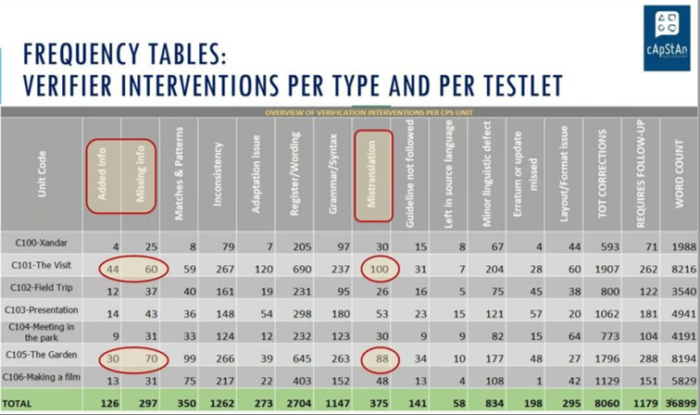

cApStan’s “Translatability Assessment” process will identify the lion’s share of potential issues upfront, before translation begins, by checking test items against a list of translatability categories, and reporting potential issues in a centralised monitoring tool. Alternative text may be proposed, but without loss of meaning. In post-translation a segment-by-segment comparison of the target to the source is carried out by trained cApStAn verifiers. A systematic use of a list of intervention categories helps them formulate a “diagnosis” and report back in a standardized way and generate relevant statistics. For example “frequency tables” will show the number of interventions that verifiers deemed necessary. If there are outliers in some units, it is most likley that the issue is in the source (see example below). In both pre- and post-translation any potential issues can be identified, and where deemed necessary, corrected.

Involve linguists and cultural brokers at item development stage

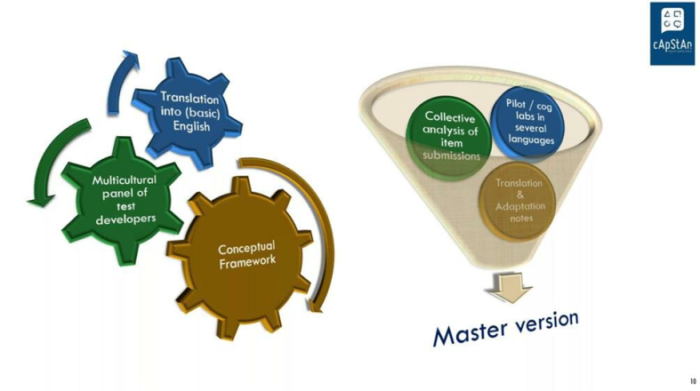

At the design stage it is very important to make item developers aware of the fact that if they are writing material that is earmarked for translation it is not the same as writing in one’s native language for an audience of native speakers of that language. For this reason, it is suggested to involve linguists and cultural brokers at the earliest possible stage of item development. In the model below a multicultural panel of developers “translates” (adapts) the test into the most basic English possible. A language in which everything is unambiguous, clear, with no unnecessary complexities, no elegance for the sake of art. After a collective item analysis, one can proceed with pilots or cognitive labs in several languages. These will allow you to eliminate residual issues in the source version, which is no longer an English language version but an English source version to serve as a base, a starting point for other language versions. After all, there is no such thing as “universal English”. This master version may then be translated into American English for US respondents, South African English for South African respondents, etc.

Leverage translation technology and existing resources

Advances in translation technology and existing resources can – and should be – leveraged at the earliest possible stage. Translation memories, glossaries, style guides from past tests can be extremely useful in identifying and avoiding recurring and foreseeable errors.At cApStAn we use existing resources also when translating/verifying test response scales. See our article on “The challenge of translating scales in multilingual surveys and the value of leveraging legacy materials“.

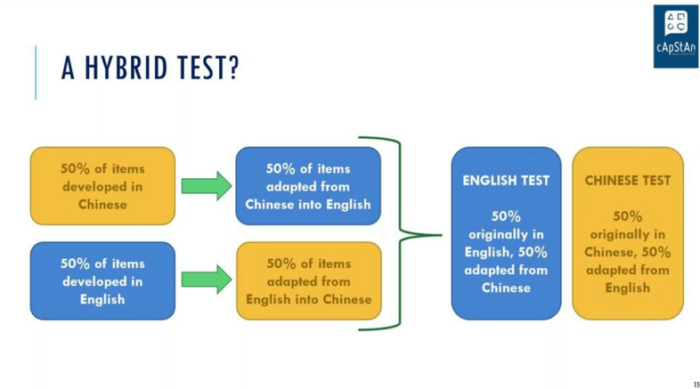

Looking to the future: the hybrid test

In the hypothetical but very promising design shown below 50% of the test is written in English and 50% in Chinese. The test in Chinese is then adapted into English and the English one into Chinese, following the same adaptation processes as any other test. This would allow test developers to see whether there is a significant difference between items that have been adapted and items that were in the original language; and it can be done in parallel for Chinese and for English. A novel approach which would really lead us way further. To be followed!

In our on-demand webinar cApStAn localization experts Steve Dept, founder & CEO, and Elica Krajčeva, Senior Project Manager cover the following points:

* How to use simplified language to produce a well-crafted English source version

* How to prepare a comprehensive corpus of adaptation notes

* How to implement a standardised adaptation design for all target versions, including an adaptation into idiomatic English for use in English-speaking regions