Stripping literary works of all but their punctuation can reveal interesting characteristics about the authors and make for beautiful art

by Pisana Ferrari – cApStAn Ambassador to the Global Village

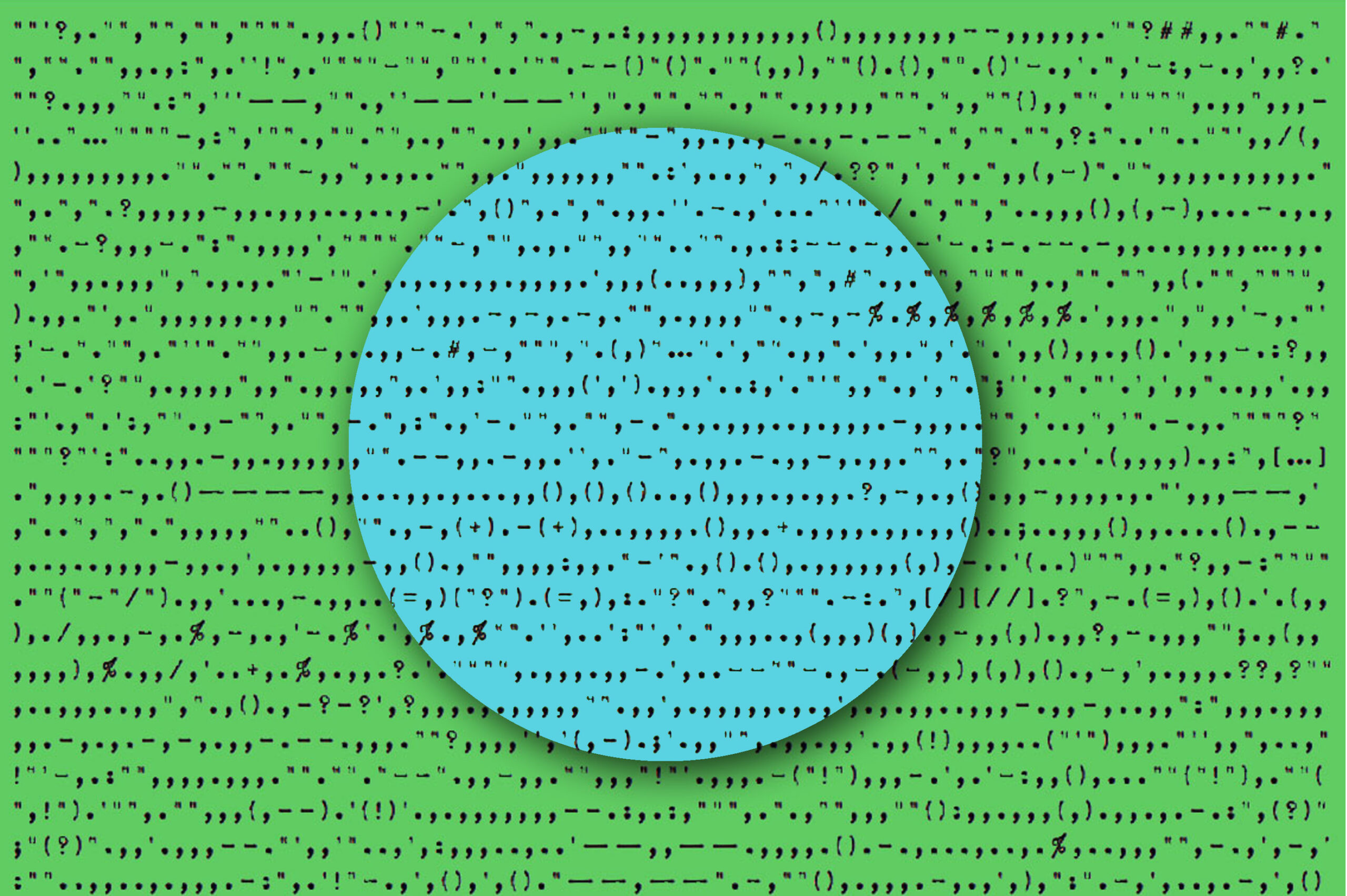

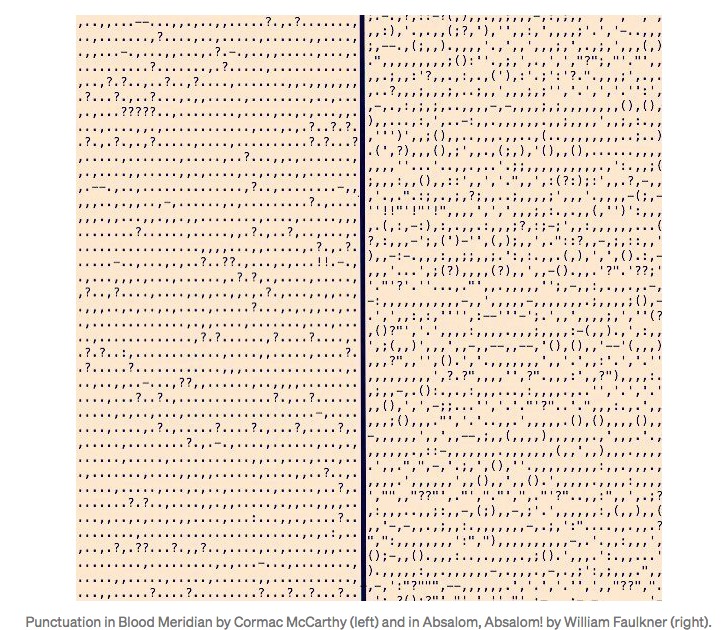

Punctuation has a very long history, often marked by divisiveness. The introduction of each new mark was met with suspicion, disdain, and sometimes even with violence (yes! read about the 1905 “Comma strike” by Moscow printers in our article at this link). As US author Mary Norris writes, in her very entertaining “Confessions of a Comma Queen”, “Punctuation is a deeply conservative club. It hardly ever admits a new member”. Punctuation marks can fall out of favour at the drop of a hat, so to speak, and many have never even caught on. More recently, it is the lack of, or its “misuse”, that is creating alarm. The age of online communication has brought about a radical reinvention of punctuation, in ways that transgress the boundaries of what is commonly defined as “good grammar”. This has sparked concerns about the future of formal language and become a hot topic of discussion (see also our article on this topic at this link). All authors, whether of literary classics or more contemporary works, have their own punctuation idiosyncrasies, of course. Extrapolating punctuation from literary works can reveal a lot of information about authors’ writing styles and habits, as well as other interesting characteristics. In 2016 Adam J. Calhoun, a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Princeton University Neuroscience Institute, presented a data visualization of a number of novels stripped of all words in an article for Medium titled “Punctuation in Novels”. “Writing can be beautiful because of the words an author chooses to use: but it can also be beautiful because of the choice of punctuation”, Calhoun says. “Why not print out all of the punctuation of Pride And Prejudice and cover your walls?”, he adds. Calhoun says he was inspired by the work of Nicholas Rougeux, a designer and artist from Chicago, who decided to see what it would look like if all the words were removed from classic pieces of literature. The result is a series of wonderful posters where punctuation marks form one continuous line of symbols, in the order in which they appear in the text, that swirl into a spiral. The posters can be viewed (and bought) at this link. See a detail of his Alice in Wonderland below (image n.2). And here is a comparison between authors Cormac McCarthy and William Faulkner’s punctuation, from Calhoun’s article (image n.1).

Image 1. Photo credit: “Punctuation in novels”, Adam J. Calhoun, Medium, Feb 15, 2016

Link: https://medium.com/@neuroecology/punctuation-in-novels-8f316d542ec4

What punctuation can tell us about an author

Calhoun wondered what his favorite books would look like without words. “Can you tell them apart or are they all a-mush?”, he asked himself. The differences were stark. “Absalom, Absalom! is wild; moreover, one might say, it is statements, within statements, within statements: who doesn’t love that?”, he says. Especially when placed next to a novel with a more simplified prose, Blood Meridian, by Cormac McCarthy. For his data visualization project Calhoun’s analysed nine different literary works, from different periods. This allowed him not only to see which punctuation marks are used the most, or the least, but also to compare which authors had the longest words or shortest words per sentence. Faulkner beat them all in terms of longest words per sentence, says Calhoun. The shortest words per sentence are in Hemingway’s “Farewell to Arms”. “How refreshing and wild that must have been”, he says, “almost no commas, just sentences, dialogue”. More recently Calhoun has also transformed the punctuation into a heatmap. Periods and question marks and exclamation marks are red. Commas and quotation marks are green. Semicolons and colons are blue. Brilliant, check out his blog.

Curious to see how your own texts looks when stripped of all but punctuation? Try this link

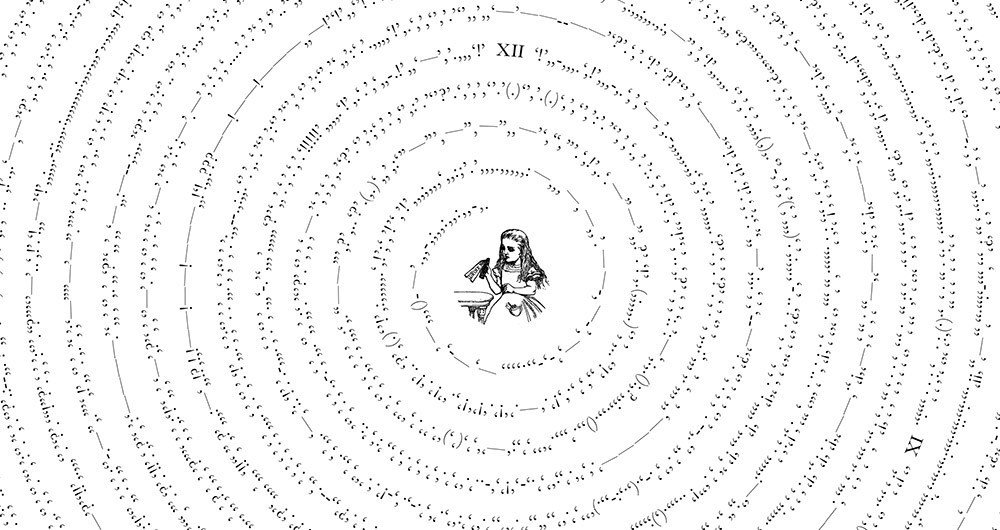

Author and journalist Clive Thomson has developed a web tool that lets you “spy” your hidden literary style, as he describes it. In a recent article for Creators’ Hub titled “What I Learned About My Writing By Seeing Only The Punctuation”, he says he processed six of his latest articles for Medium and that these reveal a number of interesting things: that he really loves to use m-dashes for dramatic emphasis, that he does not often use dialogue or quotes and that there are surprisingly few double-quotation marks. His oddest quirk? He occasional deploys super-exuberant parenthetical statements, ones that consist of several sentences, each of which ends in an exclamation point. He also writes very long parenthetical statements: one contains a hefty fourteen pieces of punctuation, including an internal colon: ( “ ‘ — “ . — . , ‘ , : , , . )! If you want to try it out on your own works Thomson suggests that for best results you should input about 6,000 to 8,000 words of text. We tried the tool ourselves, and processed several articles from our blog for the cover photo of this article. It is amazing to see how many commas (too many?) and inverted commas there are, and that there is not a single semi-colon…. “It’s also fun to use this tool, says Thomson, “to crunch prose from famous books”. He tried out the opening pages of several novels, and one thing he could spot quickly is which passages were based heavily in dialogue and which were based more on description and narrative.

Image 2. Photo credit: “Between the words. Exploring the punctuation in literary classics”

Nicholas Rougeaux, detail of “Alice in Wonderland” – https://www.c82.net/work/?id=347

Sources

“What I Learned About My Writing By Seeing Only The Punctuation”, Clive Thomson, Creators’ Hub, October 8, 2021

“Punctuation in novels”, Adam J. Calhoun, Medium, February 15, 2016

“Here’s What Classic Books Look Like Without Words”, Nicholas Rougeaux, Wired, January 19, 2016

“Between the worlds. Exploring the punctuation in literary classics”, Nicholas Rougeaux blog

Cover photo

A series of cApStAn blog articles processed by the web tool created by Clive Thomson — https://just-the-punctuation.glitch.me/ — which strips away words and leaves only puntuation, graphic elaboration by Graphillus.

See also our other articles about punctuation

A very entertaining article about the “Oxford comma”, and why we recommend using it

Confessions of a Comma Queen: “a sharply sparkling grammar guide” (Oprah Magazine)

Foreign loanwords in English and the “exotic charm” of accents