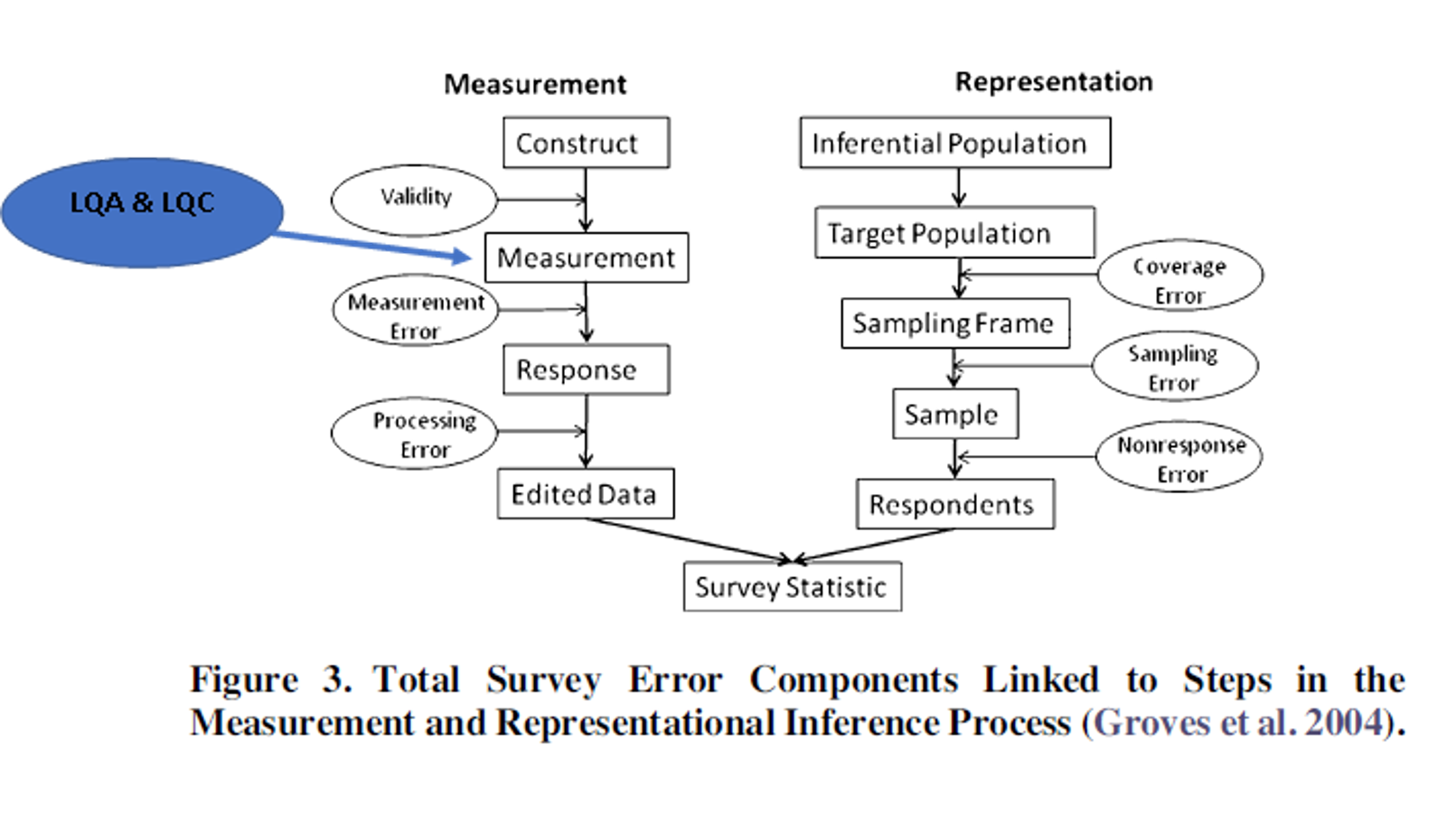

Referring to the Total Survey Error (TSE) framework when designing and monitoring translation workflows for questionnaires

Advances in survey methodology research have brought advantages to data reliability and validity, especially in the 3MC (Multinational, Multiregional, and Multicultural Contexts) surveys. The “Total Survey Error” (TSE) is the example of a paradigm that provided the conceptual framework for optimizing surveys by maximizing data quality within budgetary constraints. This framework links the different steps of a survey design, collection, and estimation, into their (potential) source of error (e.g., measurement, processing, coverage, sampling and non-response errors), helps organize and identify error sources, and estimates their relative magnitude (Biemer, 2010). It was used mostly in the design and evaluation of one-country surveys, but a more recent, adapted, TSE framework for survey research in cross-cultural contexts addresses challenges that are unique or more prominent in 3MC surveys (Pennell et al., 2017).

Not all error sources are known, some defy expression, and some can become important because of the specific study aim, such as translation errors in cross-cultural studies. These studies require a design that will ensure that the multiple language versions meet the highest standards of linguistic, cultural and functional equivalence. And, as far back as 1989, authoritative literature (Groves, R. M., “Survey errors and survey costs”), found that early identification of the translation and adaptation (localisation) potential issues could contribute to minimising the TSE and thus avoid disadvantageous “trade-off between error and costs”.

At cApStAn, in our 20+ year experience of translation and adaptation of questionnaire items for some of the world’s most prestigious organisations and companies (eg. the OECD’s PISA and PIAAC, the IEA’s PIRLS and TIMSS, the European Social Survey, EU OSHA’s WES) we have seen that it is best to address possible ambiguities in meaning, as well as idioms and colloquialisms, or any other potential translation issues, including cultural ones, very early on. That is why we make a strong case for linguists to be involved in the initial stages of the test or survey design: relatively low investments “upstream” can lead to very productive “downstream” outcomes.

Where do LQA and LQC fit into the TSE framework?

Errors due to mistranslations are a comparison error that is an interaction between the question wording components of each study (Weisberg 2005).

For example, a close translation of the English question “Does he like adventures?” in French is more likely to be understood as “Does he like amorous adventures?” Bilingual or multi-lingual researchers with substantive knowledge of two or more cultures and languages are essential in this approach. In addition, qualitative study and cognitive testing are critical for questionnaire translations. After all, the mutual understanding among the respondents is the goal (Harkness et al 2016).

In the TSE Framework, different languages and cultures are among the contextual factors that can lead to errors in measurement in international surveys. Contextual factors include local survey expertise, survey infrastructure, human resources available, survey environment and tradition, but also the population mobility, number of languages and dialects, cultural aspects that can affect response and survey environment (collectivism, privacy concerns, masculinity).

Workshops for item-designers on item-writing for international surveys, and/or translatability assessment of the draft questionnaire are upstream low investments for productive downstream outcomes.

The latest Total Survey Error framework lists translation and adaptation (localization) in the international, multilingual, multicultural surveys among the steps where measurement errors can happen.

Including Linguistic Quality Assurance(LQA) and Linguistic Quality Control (LQC) (verification) methods in a 3MC survey design decreases the response bias and other measurement errors caused by poor questionnaire design.

What is cApStAn’s modular approach to LQA and LQC in this framewrok

References

Groves, R. M. (1989). Survey errors and survey costs. New York: Wiley & Sons

Harkness, J., A., with (alphabetically) Ipek Bilgen, AnaLucía Córdova Cazar, Mengyao Hu, Lei Huang, Sunghee Lee, Mingnan Liu, Debbie Miller, Mathew Stange, Ana Villar, and Ting Yan, 2016

Questionnaire Design, Guidelines for Best Practice in Cross-Cultural Surveys. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. http://www.ccsg.isr.umich.edu/