Translating “The name of the Rose”, an example of a linguistic quality assurance process applied to literature

by Pisana Ferrari – cApStAn Ambassador to the Global Village

In 1983 Italian academic, historian, semiologist, journalist and author Umberto Eco published his first novel, Il nome della rosa (The name of the rose). The book became a literary event almost overnight and was on the best-seller list practically everywhere for months. It was translated widely and also made into a movie, in 1986, by French film director Jean-Jacques Annaud. The novel is a murder mystery set in an Italian monastery in the the 14th century, which combines semiotics in fiction, biblical analysis, medieval studies, and literary theory.

Eco is known to have worked very closely with his translators: he describes this in detail in his book Experiences in translation. In this book Eco writes that translation “is a strategy that aims to produce in a different language the same effect as the source discourse”. And, as it involves a shift between cultures, “the translator must take into account rules that are not strictly linguistic but, broadly speaking, cultural”.

In an article for the Sole 24 Ore journalist Mario Andreose writes that Eco would often meet his translators and that he provided them with a 50-page dossier, which, he adds, would in itself have been worthy of publication. In this dossier Eco indicated the meaning of some of the more challenging parts for a foreigner, details on the historical-cultural context, and possible lexical alternatives. Eco’s ongoing interaction with his translators, and the support he provided them with his dossier, were aimed at preventing potential translation issues, and preserving linguistic and cultural equivalence across different languages and cultures, much as – and here we shamelessly venture to suggest a parallel – with cApStAn’s LQA.

Drawing a parallel between Eco’s approach to translation and cApStAn’s LQA

cApStAn’s Linguistic Quality Assurance (LQA) is a set of processes designed to ensure linguistic and cultural equivalence across multiple language versions of a questionnaire or test items. It includes pre- and post-translation work as well as consultancy in translation technology. “Translatability assessment” is carried out pre-translation: it serves to prevent potential translation and adaptation issues later down the line, much as Eco’s dossier did. In some cases, cApStAn’s linguists provide translation/adaptation guidelines, propose alternative wordings for the source text, and organize workshops, in order to guide test item writers or questionnaire authors and circumvent the issues identified: here again the comparison holds. For cApStAn it is essential that a test or survey will ask the same question across different regions and cultures, so that comparable data are collected. For Eco, as indeed for all authors, translation is essential in order to share their art, vision and messages across different regions and cultures in a comparable way and in order to achieve the “same effect”, as Eco says.

Contact us if you want to learn more about our LQA processes

Does the future lie in a collaborative model of translation?

Eco is not the only author to have developed a close connection with his translators; many others had found the interaction fruitful and mutually enriching. To take a recent example, Polish author Olga Tokarczuk, winner of the 2018 Nobel prize for Literature for her novel Flights, speaks of the loneliness inherent in the work of a writer, and of the relief that comes with being able to share authorship with someone and relinquish at least part of the responsibility for a text. The translator becomes a guide, taking the writer by the hand and leading him/her across the borders of nation, language, and culture. At cApStAn we believe the future lies in a collaborative model in which test developers or questionnaire authors and linguists join forces to shape, streamline and promote best practices in test or survey localisation. Embedding translation in the test item or questionnaire development phase is vital in order to maximise cross-language comparability. It allows psychometricians and survey methodologists to take more language parameters into account and linguists more psychometric features.

To what extent should an artist’s work be influenced by his/her translator?

Tiffany Tsao spent three years translating the award-winning Sergius Seeks Bacchus, by Indonesian poet Norman Pasaribu, into English. She speaks of a close relationship with the author that was mutually nurturing and intellectually energizing. Pasaribu went so far as to rewrite two of his poems based on Tsao’s translations, and revise parts of a poem in order to “prepare” it for translation into English. At cApStAn – as we have seen above – we carry out what we call “source text optimisation” as part of our translatability assessment process. We have found that recurring translation and adaptation issues, which can affect comparability of results across different languages, can be prevented by crafting a more “translatable” original. But applying this concept to creative work is a different matter. Should an artist’s work be affected by concerns over how his work will be translated, one wonders?

Curiosities about the The name of the rose

-In the opening pages of Eco’s novel readers learn that The Name of the Rose is not a novel by Umberto Eco. Eco lets us know that he has merely translated a book given to him in 1968 by someone named Abbé Vallet, which was a French translation dated 1842 of a Latin text written by an aging monk, Adso of Melk, in 14th-century Italy. In other words, one is reading a (fictitious) Latin 14th-century text, translated into French by (the fictitious) Abbé Vallet in 1842, translated (fictitiously) again into Italian by Umberto Eco in 1980!

-One of the characters in the novel, the monk Salvatore, speaks a made-up language, composed of fragments of a variety of languages, including Latin, Spanish, Italian, German. Eco wished to convey an impression of “defamiliarisation” for the reader, and says that it was difficult for translators to render this “Babel” effect. Examples of how translators tackled the challenge are provided in his book Experiences in Translation.

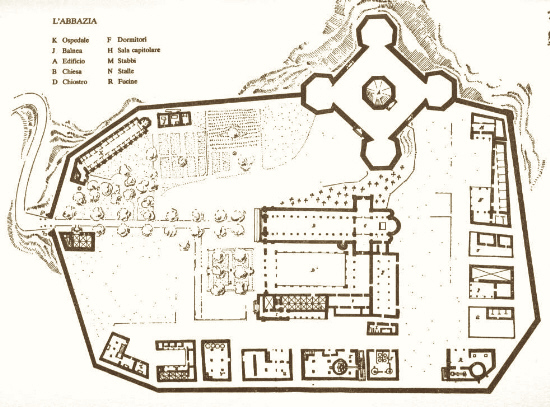

-Eco has publicly acknowledged the influence of The Library of Babel, written by Borges in 1941, on The name of the rose. His Aedificium library is of similar construction to Borges’ Library, with hexagonal rooms and ventilation shafts. In each entrance way “hangs a mirror,” and there are numerous other symbols in common with the work of Borges. The Library is peopled by librarians who are born, work, and die among the books. Both Eco and Borges were “titans of learning” whose lives were devoted to books, and Borges himself was once appointed director of the National Public Library in Buenos Aires.

-A new Italian edition of The name of Rose, which has just been released by La nave di Teseo, contains the original drawings, sketches and notes by Umberto Eco, never previously published. In an interview for Rai News a few years ago Umberto Eco explained that he did the drawings for the novel first, to create the characters and the “book’s world”, then he wrote the text.

Sources

“Experiences in Translation”, Umberto Eco, University of Toronto Press Inc., 2001

“La Rosa planetaria dei traduttori”, Mario Andreose, Sole 24 Ore, February 20, 2016

“L’importanza dei traduttori, imprescindibili mediatori culturali”, Gloria Ghioni, Il Libraio News, March 28, 2017

“Book Review: The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco”, David Fish, Medium, May 14, 2017

“It’s a silent conversation: authors and translators on their unique relationship”, Claire Armitstead, The Guardian, April 6, 2019

“Borges and The name of the rose”, Erik Ketzan, The Modern World, August 14, 2007

Photo credit: cover of Il nome della Rosa, 2020, by La nave di Teseo publisher