What are “contact languages” and why are they in danger of extinction?

by Pisana Ferrari – cApStAn Ambassador to the Global Village

When groups of people who speak different languages come together, they sometimes create a new one, combining bits of each into something new that everyone can use to communicate easily. A recent article in BBC Future warns that these “linguistic mash-ups”, better known as “contact languages”, are at high risk of extinction. From pidgins – forms of simplified speech – to the more mature, formalised creoles that have developed from them, contact languages exist all over the world. Many are closely connected to European colonial expansion and its accompanying slave trade, like Haitian Creole, Gullah Geechee, Jamaican Creole. (1) Some contact languages are transitory; others have persisted for hundreds of years. Nigerian Pidgin English, for example, is still spoken by an estimated 75 m people and allows speakers of over 500 tongues to communicate.

An overview of the status of contact languages in the world carried out by Nala H. Lee, a linguist at the National University of Singapore, found that up to 96% of contact languages are either endangered or “dormant”, having lost the last known speakers, compared to the less than 50% of the circa 7.000 total. (2) The risk of a contact language disappearing is therefore nearly double that for all languages, and today only 200 or so remain. Contact languages have traditionally commanded less respect: they are thought by many to be “bastardised” versions of the component languages from which they derive. This has had repercussions in terms of funding, or lack thereof, from international agencies dedicated to the documentation and preservation of endangered languages.

Why contact languages should be saved

All conventionally discussed consequences of language loss apply to contact languages just as they do to non-contact languages, says Lee. Language extinction affects cultural and ethnic identity, and entire traditions and knowledge die with them. The Gullah Geechee language, for example, has a unique culture that comes from descendants of the African slave trade still living on the southern Atlantic Coast of the US. Kallawaya, spoken in the highlands of Bolivia, is a mixed language that encodes 900+ species of medicinal plants. The Baba Malay-speaking communities in Malaysia, formed via marriages between Chinese traders and indigenous women, have preserved forms of ancestral worship of Chinese origin that now risk being lost. Contact languages are also a way of partially maintaining a threatened language and are important for linguists studying how languages evolve and how our brains learn to speak them.

What makes contact languages particularly fragile

In some cases it is the contact that gives rise to a language which does not last very long. Northern Territory Pidgin English, which came about through trades between British settlers in N. Australia and some Asian countries, became obsolete when trading was halted. In other cases, there have been deliberate efforts to suppress informal languages. After the annexation of Hawaii as a territory of the US in 1898, for example, Hawaiian Pidgin and the indigenous Hawaiian were banned use in schools and government (Hawaian is now one of the official languages and Hawaiian Pidgin is widely used). Contact languages are mostly spoken in informal settings and passed on orally. They are unlikely to be written down or used in official documents and can fade away as younger generations move to seek work elsewhere. On the US Virgin Islands, English gradually took over and Negerhollands, a creole dating back to 1700, combining Dutch, English, French, Spanish and African languages, became extinct in 1987.

What of the future of contact languages?

Lee laments that there has been a pervasive tendency to privilege “autonomous” languages over those that lexically derive from existing languages. Luckily there are a number of indigenous groups, international agencies, independent non-profits, academics and others working to preserve them. Among these, the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission, the Sri Lanka Malay Association the Creole Heritage Center. There have also been moves to legitimise some contact languages: in 1987, the government of Haiti made Haitian Creole an official language alongside French. Similar efforts are currently underway in Jamaica. But there are tongues like Baba Malay that only older generations have held onto. That includes Lee’s own grandparents. As these languages diminish, so do the cultures that created them.

The case of Nigerian Pidgin English

Not all contact languages are endangered. Nigerian Pidgin English (NPE) has actually thrived in past decades. It is a hybrid of English and several local ancestral languages. More than 75 million people are believed to speak NPE across Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea. Its use is widespread among all social classes and is increasingly popular among young people, writers, politicians and musicians. It is also used by the diasporic communities in US, Canada and UK and some countries in Europe. It is not yet recognised as an official language in the country, despite efforts by activists. In 2017, BBC started services in NPE, BBC News Pidgin. Naija Lingo is an online Dictionary whose editors claim NPE it is on the verge of becoming a full fledge language of its own, and ask for contributors to be part “of this revolution”.

Footnotes

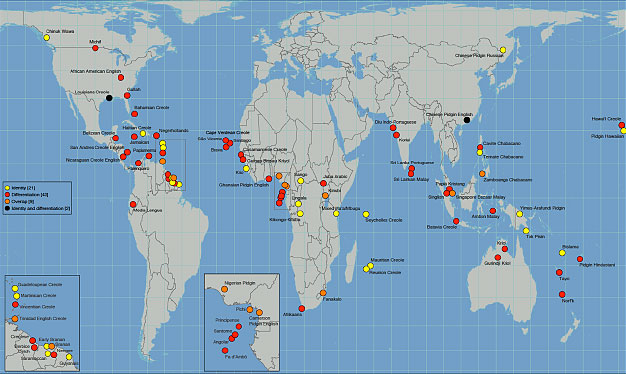

1) For several years an international team headed by the Max Planck Institute surveyed 25 languages in the Western Hemisphere, 25 African languages and 26 Asia-Pacific languages. The team collected the data and represented in on an atlas with 130 maps, to show the distribution of grammatical and sociolinguistic information. They found that many of the maps showed striking similarities between grammar used in languages like Caribbean Jamaican Creole or Haitian Creole and African languages. The latter were slaves, who were shipped to America in the 17th century. Since the vast majority of slaves were transported to the Caribbean colonies and the southern United States, the grammar of Caribbean languages resembles the West African languages in many ways.

2) Nala H. Lee has identified 82 contact languages at some level of risk. A total of 11 are critically endangered: Baba Malay, Chinook Wawa, Javindo, Kodiak Russian Creole, Macao Portuguese Creole, Michif, Petjo, Principense, San Miguel Creole French, Malabar-Sri Lanka Portuguese, and Yimas-Arafundi Pidgin. An additional 5 languages are severely endangered: Cavite Chabacano, Kallawaya, Louisiana Creole,Ngatik Men’s Creole and Singapore Bazaar Malay. Another 6 languages are endangered: Diu Indo-Portuguese, Malaccan Creole Portuguese, Sri Lanka Malay, Ternate Chabacano, Wutunhua, and Yilan Creole. A total of 21 languages are threatened: Angolar, Babalia Creole Arabic, Casamancese Creole, Fanakalo, Gullah, GurindjiKriol, Iha Based Pidgin, Kinubi, Korlai, Kriol, Mbugu, Media Lengua, Nauru Pacific Pidgin, Norf’k, Palenquero, Pidgin Hindustani, San Andres Creole English, Santome, Saramaccan, Sranan, and Tayo. The remaining 39 languages are vulnerable.

Sources

“The fragile state of ‘contact languages'”, John Wenz, BBC Future, 2nd September 2020

“The Status of Endangered Contact Languages of the World”, Nala H. Lee, Annual Review of Linguistics 2020, 6:1, 301-318

“Nigerian Pidgin English”, Francesco Goglia, University of Manchester Working group of Language Contact

“Nigerian Pidgin English”, Terminology Coordination blog, European Parliament, April 3, 2018

Atlas of Pidgin and Creole Language Structures (APiCS), Mac Planck Institute, Leipzig, Germany

Photo credit: Map from the “Atlas of Pidgin and Creole Language Structures (APiCS)”, Mac Planck Institute, Leipzig, Germany